Zoom had a moment back in 2020, when everyone started moving their meetings out of the boardroom and onto the kitchen table. There followed a rash of podcast recordings with choppy audio, lag, and crosstalk.

The last two can be solved with good editing. The first can be solved with just a few clicks in Zoom. Here’s how to set it all up.

Before recording, enable separate audio files

Good podcast editing involves making sure everyone sounds their best. In order to do that in an audio editing app, each person’s voice needs to be on a separate track. That way, if one person’s really loud, you can increase their volume without affecting the other tracks. Got a guest whose laptop fans are spinning? Apply noise reduction just to their track.

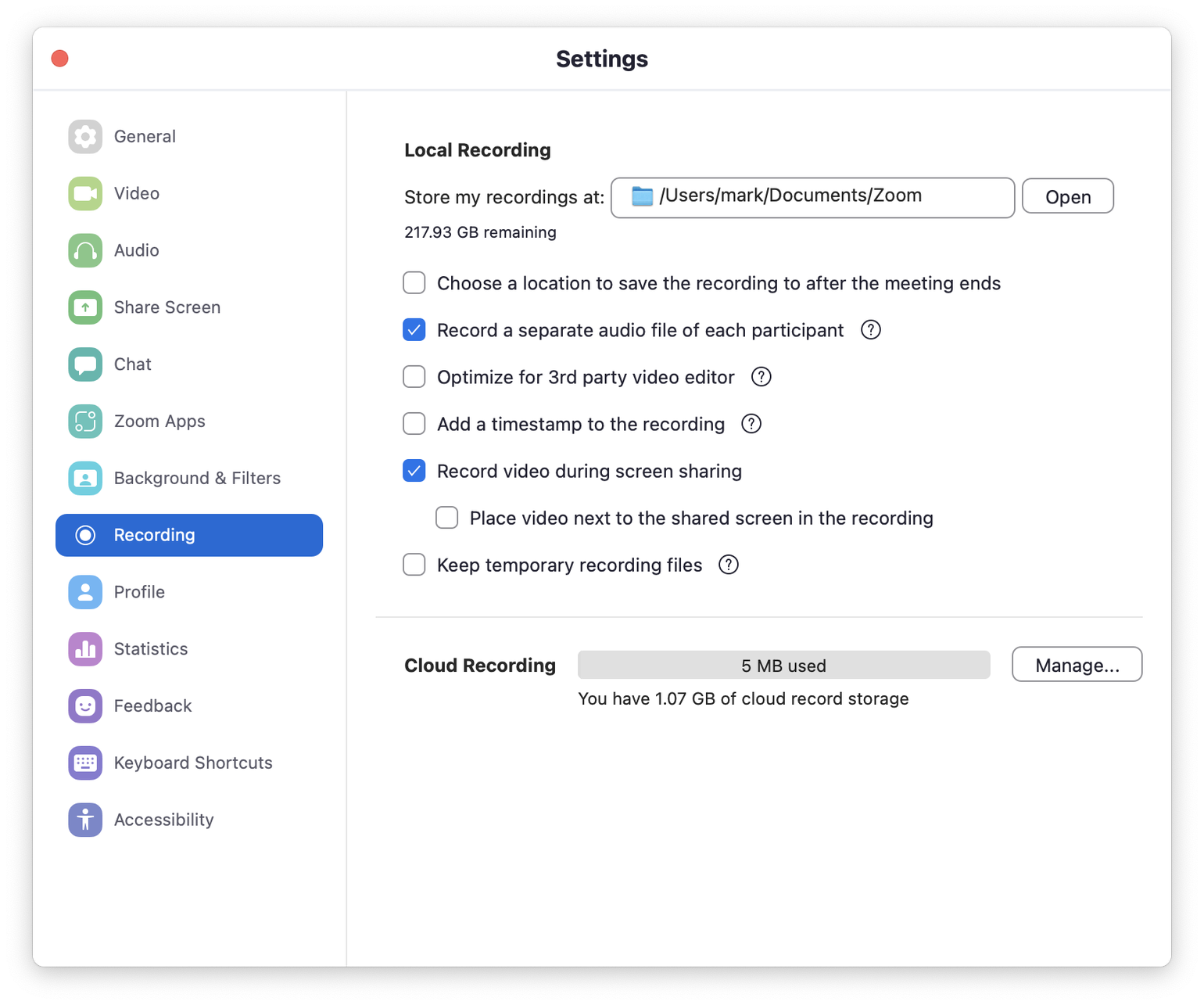

By default, Zoom will record everyone to one single audio file. So the first thing we need to do is tell Zoom we want a separate file for each person speaking. To do that, open your Zoom preferences, head to the “Recording” tab, and tick this setting:

☑️ Record a separate audio file of each participant

When you’ve finished recording your episode and closed the meeting, Zoom will give you a folder with audio files named after each participant in the call. Drag those into your audio editor, and you can make any per-track adjustments you need to.

This is also the best way to beat crosstalk: where two people are talking at the same time. In your audio editor, you can simply cut out the unwanted voice, and it’s like it never happened.

Get the best audio quality possible

While the previous tip was just for the person recording the conversation, the next bit is something every participant should do before the recording begins.

Zoom is video conferencing software, built to make sure the human voice is loud and clear. This can involve some aggressive noise reduction, and a reduction in audio quality to save bandwidth. That doesn’t always provide us the most pleasant listening experience, so here’s how we can get better sound from your Zoom recordings.

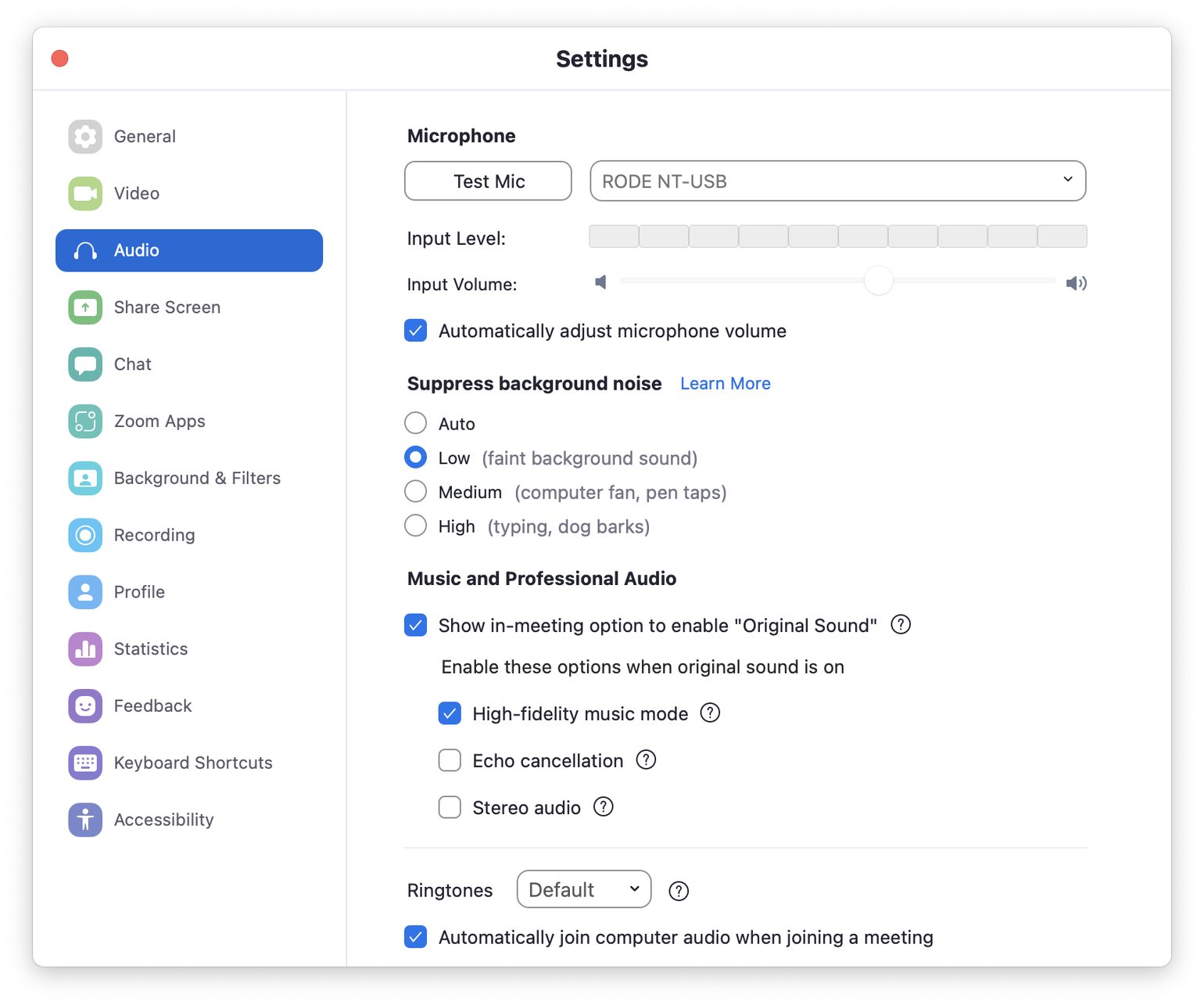

- Open Zoom and go to Preferences.

- Click the “Audio” tab.

- Make sure the speaker is set to the desired output (usually “Built-in output” or “System default”).

- Make sure the Microphone input is set to the guest’s mic.

- Under the “Suppress background noise” option, select “Low”.

- Under “Music and professional audio”:

- Tick “Show in-meeting option to enable “Original sound”.

- Tick “High-fidelity music mode”.

- Untick “Echo cancellation”.

- Untick “Stereo audio”.

Finally, when inside the call, enable “Original sound”. Again, this is something each participant on the call needs to do, not just the host.

Why we turn off Zoom’s background noise filter

When dealing with any kind of digital media – audio, video, or still images – we always want to capture the source material in its rawest form. Imagine taking a photo with an Instagram filter already baked into the image. If you wanted to make adjustments to that image, you’re putting a filter on a filter, which will result in a lower-quality image.

The same is true of audio. As podcast editors, we want to deal with the human voice in its raw form, so we can make adjustments to it ourselves, that match our workflow, and the sound we want to create. That will include background noise reduction, but at a far higher quality level than what Zoom can provide. Zoom’s noise reduction is far more aggressive than we’re likely to need, and because it’s focusing on making people intelligible, it can remove some frequencies we want to preserve.

Zoom’s filter is intended to remove things like dogs barking and people typing. Ideally these shouldn’t happen while a guest is speaking. If they happen while someone else is speaking, we can remove that part of the audio since everyone’s on a separate track. If a dog started barking in the room of the person speaking, not even Zoom would be able to fix it.

You and your guest should feel free re-enable Zoom’s background noise filter after the call. It’s perfect for its intended use – it’s just too aggressive for our purposes.

Why we enable “High fidelity music mode”

Zoom’s high fidelity mode increases the audio bitrate to 96kbps for mono recordings. That’s not the highest possible quality, but it’s pretty good for our purposes. Most podcast audio only needs to be 64kbps mono, since the human voice is mono, not stereo. That gives us a little bit of headroom to play with, so the audio doesn’t sound double-compressed.

You probably won’t notice a huge difference, but it will help with some of the higher-pitched sounds like Ss, and it usually copes better with low-volume audio.

Why we disable echo cancellation

Echo cancellation is the way Zoom tries to cope with people on a call who aren’t wearing headphones, which is how most of us, most of the time. It works on each person’s computer by listening to the sounds of the call coming from the speaker (as it’s picked up by the mic), and digitally removing it. This has to be done live, so it can sometimes be a little clumsy, and doesn’t always work. If you’ve heard yourself back half-a-second later while speaking on a Zoom call, that’s because someone’s echo cancellation isn’t working.

We want Zoom to make as few changes to our audio as possible, and avoid it mistaking crosstalk for audio it should remove. There might be a good reason why two or more people are speaking at the same time, but with echo cancellation turned on, it’s like trying to squeeze three people into a cat flap.

We can safely disable echo cancellation because you and your guests are wearing headphones. Right? If someone isn’t wearing headphones, you’ll have a nightmare in editing, because their track will contain their voice and everyone else’s. As politely as you can, you should insist that every participant wears headphones. Cheap ones are fine, and fashion or vanity aren’t excuses (you’d be surprised how often it comes up).

Why we turn off stereo sound

The human voice is mono, as are musical instruments and anything that has a single point of origin. You might choose to use stereo panning later to distinguish one voice from another, but when you’re recording the human voice over the Internet, recording in stereo is using up twice the bandwidth it needs to.

Add your response