Timing is an art and a science, and even if some of it comes naturally to you, it takes practise, so read this guide and make a space for the ideas, but don’t feel you have to cling too closely to them, especially right away; these are just useful rules-of-thumb.

Think of planning and recording an episode a little like pitching a tent. The bullet-points in your recording notes, your episode plan or your running order – whichever terminology you feel more comfortable with – are like the poles holding up the fabric of the tent, or in our case, the conversation. The structure is there to aid the conversation, but shouldn’t impede it.

As your show evolves, each tent will have a slightly stronger structure, with poles planted firmly in the ground, keeping the canvas from blowing away, but not holding it down too tightly.

Fine, but how do you actually plan an episode?

As we covered in the piece about episode length, the object is to communicate an idea efficiently but comfortably, rather than filling a half-hour time slot. So start with a single topic or idea, and use that as your springboard. We’ll call this your “main concept”.

If you’re covering the week’s news, then your main concept is the news of the week, whereas an evergreen podcast about dog fostering might have dog-walking as the main concept for its first episode, dental hygiene for the next, caring for the coat as the next, and so on. The idea is to give each episode a clear focus.

Solve a listener’s problem

If your podcast imparts knowledge, imagine what a prospective listener might Google in order to find the episode you’re planning, and try and base your episode around that question.

At this point we’re not thinking in terms of SEO, but instead about the knowledge gap that your episode will bridge. For our dog fostering podcast, let’s think about the sense of loss a foster carer might feel once their dog has found a new home. What would someone search if they foster dogs and they’re worried about this aspect? How can our episode tackle or at least define that problem?

Most questions don’t have a simple answer, so don’t feel pigeon-holed or forced into having to create some sort of super-keyword-optimised listicle in audio form. Instead, work backwards, look at the context or the underlying factors someone needs to address before even asking the question.

So often, the answer to a complex question is “it depends”. So, what does your answer depend on? What are the different ways that question could be asked, for people under different circumstances? What are the related questions?

Make space for the guest

If you have a guest, give them the space to answer these questions, and to solve your listeners’ problem. Here, your job is to set your guest up for success, and give them the tools to address your episode’s main concept. You probably already know this, but it’s worth stating that when you have a guest, your job is to make the guest look their best, not for you to demonstrate how much you know.

When you have a guest, you become the listener’s advocate – you’re asking the question the listener can’t. Yes, you, the listener and your guest all know you know the answer to a particular question, but we want to hear the guest answer it. Don’t be afraid – in fact, be thoroughly encouraged – to ask the dumb questions. No-one will think you’re dumb for asking the simple questions, because in this instant, you’r not the expert, you’re the guide, leading us to the top of the mountain, where the expert lives.

Make a note of the guest’s name and how to pronounce it, take a copy of their photo – making sure they’re happy for you to use it – and a short bio. Also ask for their preferred pronoun before you hit Record or start promoting the episode ahead of time.

An onboarding form can help with these tasks. A simple TypeForm or a Google Form connected to a Google Sheets document works. Even an email with a list of bullet-points. Just don’t make your guest fill in a Word document and send it back, as that’s too much hassle. If you use a tool like Calendly for scheduling, you can build this onboarding into the process of arranging your recording time.

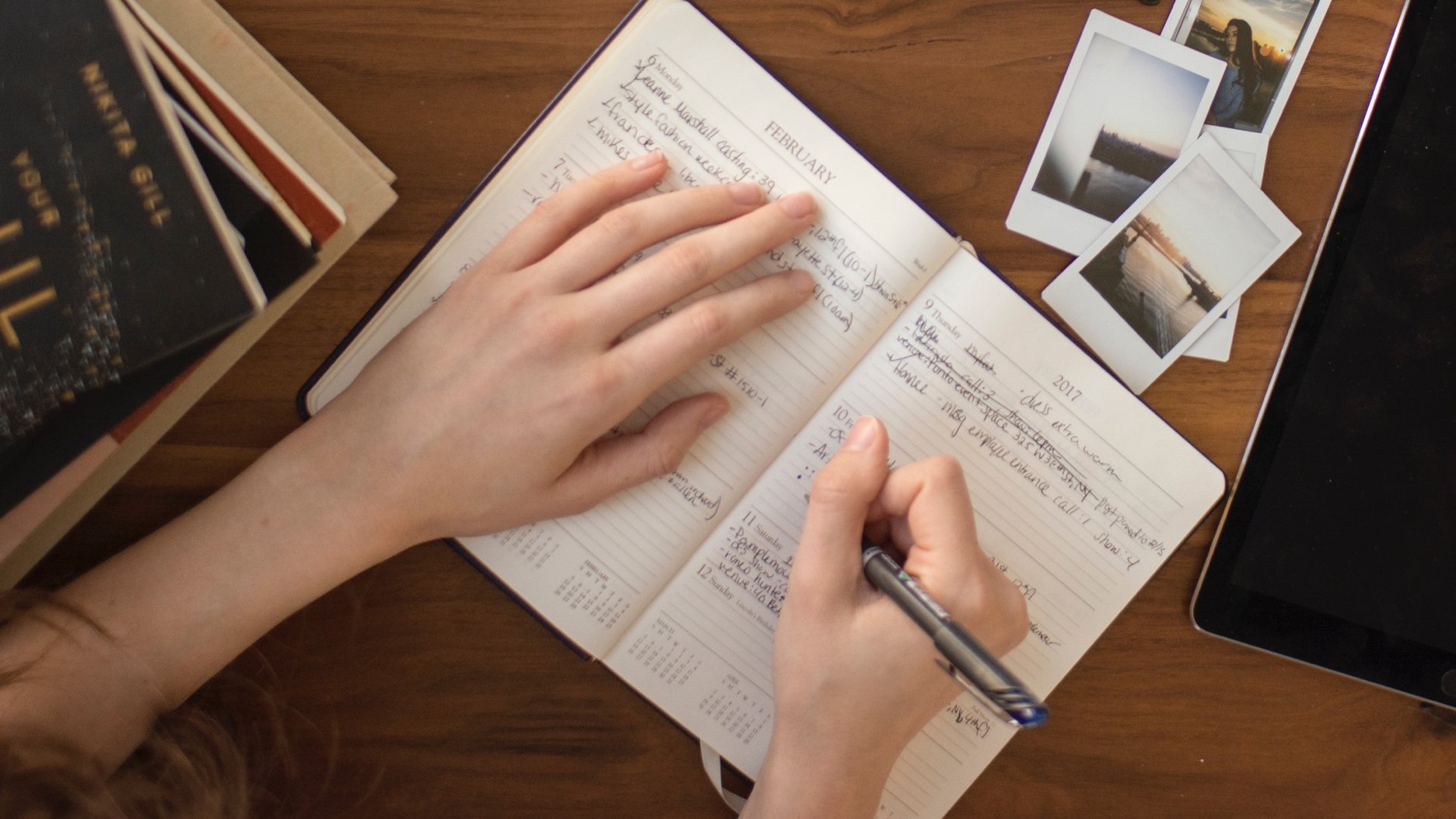

Taking notes as you go

This one might feel like a bit of an advanced method, so don’t feel you have to do this if it feels like too much to worry about while you’re maintaining an entertaining conversation with another human being. But, some people like to take notes about the episode they’re recording, to help them in the editing process later. This is especially useful if you’re working with an editor, or it might be a number of weeks before you sit down to edit the episode.

Whatever tool you use to record your episode, be it Quicktime player on your Mac or a remote recording tool like SquadCast.fm, note down the timecode of the moment you need addressed. Maybe someone said something you think should be cut, or there was a loud noise or a stumble that can be removed. Not everyone edits by listening through the entirety of the episode, so giving clear notes to your editor – or helping your future self – will make the process more efficient.

If messing around with timecodes feels like too much hard work, just note down the time, then when you’re finished with your recording, spend a moment going back through your notes and adjusting them so that they’re relative to the recording timecodes. But try to be as exact as possible. Of course, you can always listen back to the recording over a nice cup of tea and a slice of cake, make some notes while you’re feeling more relaxed, and then you’ve saved yourself and/or your editor a lot of future headaches. And you’ve had a slice of cake to boot.

Committing it to paper

Your episode plan needs to live somewhere outside of your head, because it’s really easy for simple things to be forgotten when you’re in the middle of a call with a guest or a co-host. Plus it gives your other participants a chance to follow along, to know when they might be able to chime in, or when you’re looking to bring the episode to a close.

The level of detail in your notes will depend on your particular style, and the style of the podcast itself. Some shows work well with just a list of links as a prompt for things to discuss, other shows use a skeleton script (like This is Spinal Tap or Curb Your Enthusiasm ), and some – even non-fiction – are fully-scripted. Ultimately it’s about what makes you the most comfortable.

The video that accompanies this article, for example, uses a skeleton script. Bullet-points keep the basic shape and stop the episode from diving down a rabbit hole; it’s then edited to keep it relatively tidy. Most of the work for each piece is writing the article, turning the slightly meandering speech into more purposeful text.

If you plan to intro or outro each episode in the same way, make sure to put that in your notes, making the wording as close as possible to what you’ll actually say on mic. If there are certain calls-to-action you want people to take note of – like rating and reviewing the podcast or visiting your Patreon – add these to your document to be sure you’re going to hit them.

Some note-taking apps like Bear and Notion support tick boxes, that don’t have any particular semantic meaning (maybe they’ll put a line through the proceeding text if the box is ticked). Ticking off an item once you’ve recorded it feels surprisingly good, and will help you see at a moment’s glance how much you’ve covered, and what there still is left to do.

From recording notes to show notes

Good notes can turn into good episode descriptions, or as they’re often referred to, “show notes”. This is the text that appears in podcast apps when listening to an episode, and should be on the canonical webpage for each episode (we’ll cover that in a later article).

Any links you gather along with quotes or snatches of text, any bullet-points that hint at an episode structure can all inform the description you compile for your episode. A well-written, well-structured description makes your episode more attractive to search engines, as they still largely prefer text over speech.

If you cover a particular news story or you have a book recommendation, make sure to link it in your show notes, along with links your guests recommend or want to promote.

It’s a process

There feels like a lot to consider, but again, don’t feel this is stuff you have to implement from day one.

Do start by planning your first episode in as detailed a manner as you can stand – before it feels like you’ve planned the joy out of it, or you’re super-bored. Your first episode doesn’t have to be perfect, regardless of what people say about first impressions. Once you’ve got a plan that feels workable, each week you can make tiny adjustments to it, based on what you’ve learned, and what works best for you and your team.

In other words, treat the plan for episode one like a template. Each week is an opportunity to adjust that template just a little bit so that it becomes both more solid and foundational, but at the same time more flexible. You’ll get a feel for it, the more you record.

And if a session doesn’t go to plan, don’t sweat it. You might plan a thoroughly interesting discussion with a guest on topic A, only to find you end up talking entirely about topic B, never addressing topic A at all. If the conversation was informative and engaging, you’re about 90% of the way to a great episode. If it didn’t work out, no-one says you have to use the audio, just because you recorded it.

A structured episode plan is a north star to aim for, not a set motorway markings you have to stick to in order to avoid a crash. Just keep an eye on the road and a hand on the wheel, and make tiny adjustments to keep you on course.

Add your response